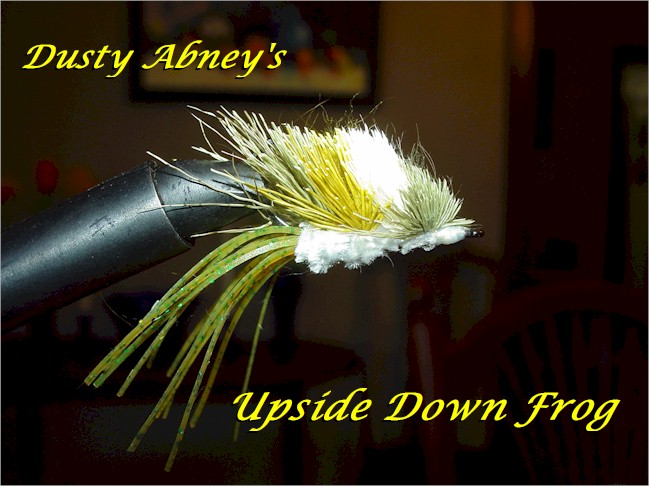

Fly Tying Dusty Abney’s Upsidedown Frog – The Story

By Dusty Abney

Dusty at his vise

Sometimes innovation is driven by jealousy. Being one of the only fly anglers on a lake covered by the crank and yank crowd can drive a fellow to think in directions his mind normally wouldn’t take. My quest seemed simple enough: find a bass bug that could be cast into heavy vegetation to draw the interest of a hungry largemouth bass. My home water,LakeAthensin easternTexas, is home to a diverse population of aquatic vegetation which holds some lovely bream and baitfish, which, in turn, attracts the black bass I so love to catch. Coincidentally, this vegetation also helplessly snags just about any fly or bug cast into it. The conventional bass fishermen have a whole host of lures that they can effortlessly cast into the weeds and then retrieve with nary a leaf in sight. Thus began my search for a more weedless fly rod solution.

I began in the logical way that most have tried and that seems to work well enough for them. The monofilament weed guard has a history that is probably almost as long as monofilament line itself. I tried every variation I could find. Single loop, double loops, a single strand tied directly to the hook shank so that it would lay in front of the hook point, double “V” strands, if it involved lashing a piece of mono to the hook to ward off the evil green stuff, I tried it. Many of these methods did, in fact, work well as a weed guard, but I had the same issue I have seen reported again and again online. If it was an effective weedguard, then it usually ended up being a pretty effective fish-guard as well. It was with a mixture of frustration, anguish, and relief that I abandoned the mono-based vein of my weedless research entirely.

At about this time in my fly lashing career I ran across the work ofGeorge Glazener. George is an evangelist of the school of hook point up flies, specifically those using 60 degree jig hooks. A fly offering riding hook point up usually results in a more securely hooked fish, and, more importantly to me, tends to be more weedless. George was kind enough to tutor me via the internet in my clumsy attempts to find the Holy Grail of weedless bass flies. He even went so far as to send me a selection of jig hooks when it became apparent to him that I was going to continue to use pliers to bend normal hooks into that configuration.

With George’s help and that of others in my internet circle of friends, I came up with a couple of patterns that worked…sort of. If I was lucky enough for the hook point up flies to land hook point up in the weeds, they skated through in a fairly weedless manner. However, if they landed in any other position, or turned the slightest bit, I was back to where I started. It was frustrating to say the least.

I began to look into Bendback patterns, including one that I found that used bucktail as a kind of rudimentary weedguard. These patterns streaked through the underwater weeds in a most impressive way, but they were not without their drawbacks. I couldn’t seem to come up with a Bendback bug that would land well on the lily pads or other surface vegetation. I had to again find my pliers to bend the hooks into submission, thus creating a potential weak point at the bend. Finally, and worst of all, when I did strike a fish with a Bendback pattern, setting the hook properly seemed to be impossible for me.

At about the time I was ready to give up and find some way to modify a rubber bait-casting frog to work on the fly rod I discovered two similar patterns at about the same time. Kevin Doran’s KDM Rat was featured in Bass the Movie and a semi-random internet search allowed me to find a single post on aCaliforniafly fishing forum about another similar bug called the Mat Buster. Both of these patterns looked just like what I had been searching for all this time. They rode hook point up, they looked like bass forage, and they had an effective weedguard I had not ever considered before: deer hair. Unfortunately, being unable to find any information on either pattern other than a few small pictures, I was left to my own devices to figure out how to tie something similar.

What resulted was a mishmash of the two patterns with a feature or two foist upon me by necessity of my poor technique. From my observations the KDR Rat had a body that seemed to be completely composed of spun deer hair trimmed closely on the “bottom” of the shank so as to help it ride hook point up. A thin piece of sheet lead was glued to the closely trimmed deer hair to give it a “keel” and reinforce the position of the bug in the water. The two pictures of the Mat Buster I could find showed only a spun deer hair head, but with chenille wrapped hook shank and a rabbit strip tail.

The reduction in the amount of hair spinning required attracted me to the Mat Buster, but I liked the keel idea of the KDR Rat. I liked the tail on the Mat Buster, but I really dislike how any but the shortest length of rabbit casts when it is wet.

With these thoughts in mind, I sat in front of my vise, bobbin in hand, and begin lashing my personal Frankenstein together. I am a big fan of spinner bait skirts in my fly tying. The action and durability it gives to an artificial is proven every day by the conventional bass anglers and it is available in any color you could ever want. In an all too brief, and all too rare, flash of brilliance, it occurred to me that tying the skirt to the “bottom” of the hook would cause its weight to add to the keel effect I wanted. But if I wanted a keel, why not add some lead wire to the hook shank before the skirt? I couldn’t very well leave that lead wire and the huge wad of skirt on the hook shank to hang on weeds, so, just like the Mat Buster I covered the hook shank with chenille.

It occurred to me at this point that I had covered the very hook shank that I meant to spin deer hair on with chenille. Out of sheer frustration at my inability to think one step ahead, I wrapped the thread back over the chenille to just under the hook point and stopped. This next part was not brilliance; it was sheer anger and serendipity acting together. Just to finish the bug so I could start from a clean slate on the next one, I grabbed a bundle of deer hair and placed it along the shank of the hook so I could flare it into place. That seemed to be the quickest way to get this nonsense over with so I could get back to my fly lashing research. I kept moving the thread forward to the eye of the hook, adding about four bundles of deer hair in total.

As I hurriedly, and not just a little angrily, whip finished the bug, I had my epiphany. All the deer hair was ON TOP of the hook. Viewed from the front, it looked like the hull of a ship, with the lead wrapped hook shank as the keel.

I immediately ran to the sink and filled it with water. Once the surface was perfectly calm, I ever so carefully placed the bug into the water. It stayed hook point up. I thoroughly waterlogged the bug and dropped it from a couple of feet back into the water with the same result. I dropped it hook point down into the water and it righted itself. I played in that sink for a good thirty minutes like a kid making mud pies. It is a very good thing my wife was not home because she probably would have had me taken away.

As is my nature, I could not leave well enough alone, so I used Mr. Doran’s idea of the sheet lead on the bottom of the bug. My gluing technique was wanting and the lead I used was prone to hanging on vegetation, so the additional lead did not last very long. The bug cast much better without it. It also skated across and through the vegetation with nary a hitch.

In the water, the bug had a tendency to sit with its rear end nice and low, with the skirt dancing in a most tantalizing manner. Every little twitch given to it by stripping line was transmitted to the skirt. The ship’s-hull body could make anything from a huge wake to the tiniest of ripples. It looked positively evil in the water.

I should not have been surprised by how well the hook point up configuration worked with regard to the actual hooking of the fish. The great majority of the fish I’ve caught on this pattern are hooked very solidly in the corner of the mouth with the distant runner up being in the upper jaw. In the time I have used this bug so far, I have not had a single fish throw the hook. It is everything I wanted in a bass bug.

I hope someone finds a niche for this pattern in pursuing fish other than just largemouth bass. I can see this being the base for a very effective mouse pattern for trout, or as a struggling baitfish pattern for pike. Any fish that you have ever struggled to catch because they were in deep vegetative cover could be a target for some variation of the Upside Down Frog.