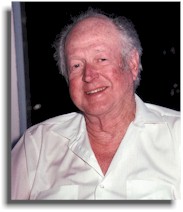

On the morning of Wednesday, May 28, Del Brown , Legendary saltwater fly-fisherman, died of a heart attack in his home in Watsonville, California. At 84, he was exceptionally spry and in good shape, still fishing hard and snow skiing every winter. In fact, he had just returned from a striper trip and was making plans for his next one.

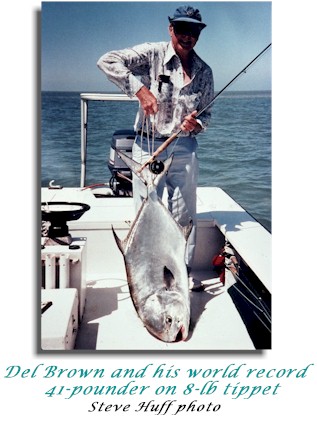

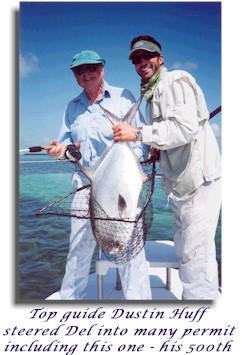

Del was the consummate peripatetic angler, never home for long. He fished more than a hundred days a year in the Florida Keys, pursuing permit almost to the exclusion of other flats species. They were his passion. His life’s goal of catching 500 permit on the fly was reached and surpassed; and at the time of his death the tally was 513 permit taken on a fly – an achievement many consider to be the single greatest accomplishment in marine fly fishing, one that may never be equaled. His famous crab fly and how he fished it is what made this happen, and it opened the door to all who covet permit on the fly. His world-record permit and tarpon have raised the bar to almost unreachable.

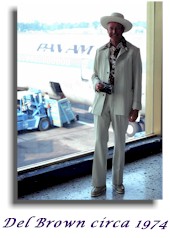

Delmar F. Brown was born December 5, 1918, in San Francisco, where he lived and worked until he married Doris Martinelli, his wife of almost 60 years. Joining the Martinelli family business, S. Martinelli and Company, upon their marriage, he served as plant manager at the apple juice and cider company, located in Watsonville, for decades before retiring.

Though proud of his angling accomplishments, Del rarely boasted, mentoring instead, sharing his decades of angling experiences gained worldwide with countless fly-fishers. While many perceived Del as only a saltwater fly-fisherman, he actually was one of the most diverse of fly-anglers, loving to catch anything on fly from panfish to billfish, especially species considered difficult to catch on fly. He particularly loved fishing surface flies and poppers.

Del is survived by his wife, Doris, his daughter, Sylvia, his sons, Peter and Doug, and his granddaughters, Alexandra and Isabel.

Del will be missed by his loved ones and by innumerable friends. He was a special friend, one with whom I spent hours sharing a skiff or sport-fisher, long phone conversations about a new fly idea, or the details of a recent trip. I’ll miss Del and being updated on his latest permit count. God bless you, Del…

Dan Blanton

The following article was written nearly a decade ago but not much has changed in terms of the advice Del Brown offers in it. At the time of his death he had landed 513 permit on fly. I have not edited the article from its original form – Dan Blanton

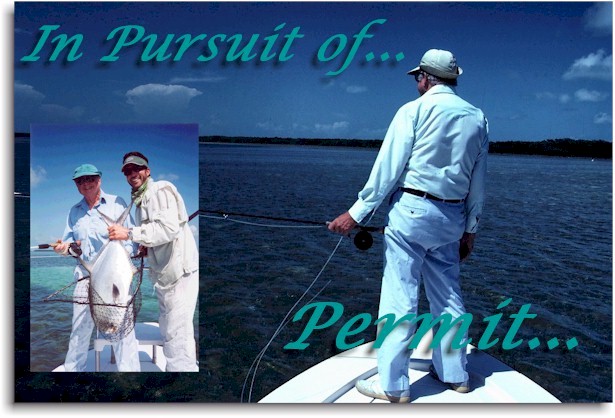

In Pursuit of Permit – Lessons from the Master

By Dan Blanton

The Permit of tropical saltwater flats – not those found over deep-water wrecks or in “blue holes”, is considered the ultimate challenge for the fly angler. They are the most difficult of all thin water quarry -nervous, wary and the most scrutinizing when it comes to the fly. To take them consistently requires skill, knowledge and a dedicated mindset, pursuing them to the exclusion of all other species.

The Permit of tropical saltwater flats – not those found over deep-water wrecks or in “blue holes”, is considered the ultimate challenge for the fly angler. They are the most difficult of all thin water quarry -nervous, wary and the most scrutinizing when it comes to the fly. To take them consistently requires skill, knowledge and a dedicated mindset, pursuing them to the exclusion of all other species.

Flats Permit are the status symbol of saltwater fly-fishing; the fish that gives credentials to one’s skill and angling stature. They are the true “Ghost of the Flats”, as difficult to see, catch and to hold as any phantom…

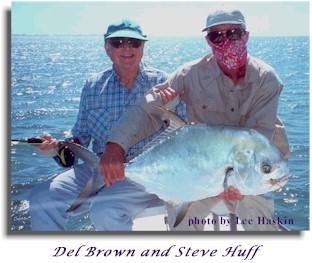

Del Brown is the most successful permit fly-rodder in history, having 354 permit to his credit, three of which are world records: a 9-3/4-pounder on 2-pound tippet, a 24-pounder on four, and the bruiser, a 41-pounder on eight. Indeed, Del knows what he is doing; and what he knows is what this article is all about.

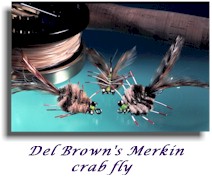

I’ve known Del Brown for more than 25 years and have tremendous respect and admiration for his fly fishing knowledge and skill. He is a commensurate fly angler in all venues. An innovator with few peers, he has developed many useful things with regard to tackle, equipment and technique, including several productive saltwater flies. If Del Brown is the top gun in permit circles, then his “Merkin” permit fly holds similar rank when it comes to productive crab monikers. It is definitely number one – the score says it all…

I’ve known Del Brown for more than 25 years and have tremendous respect and admiration for his fly fishing knowledge and skill. He is a commensurate fly angler in all venues. An innovator with few peers, he has developed many useful things with regard to tackle, equipment and technique, including several productive saltwater flies. If Del Brown is the top gun in permit circles, then his “Merkin” permit fly holds similar rank when it comes to productive crab monikers. It is definitely number one – the score says it all…

Del was born in San Francisco in 1918, has been married to his lovely and gracious wife, Doris, for 54 years, and has lived in Watsonville, California for the past 52 years, where he has managed the Martinelli apple cider plant, a family-owned operation. They have two sons and a daughter, none of which are serious anglers, thank God, since we don’t need the additional competition.

No stranger to a fly rod, Del has pursued the sport with a fervent passion for more than 50 years, 45 of which have been in saltwater, beginning with San Francisco Bay stripers in 1950.

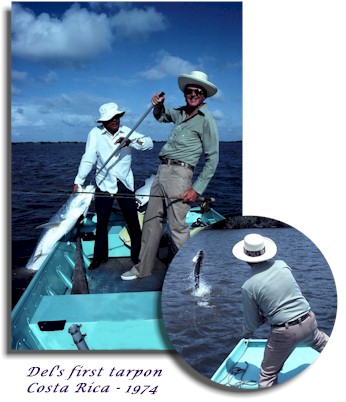

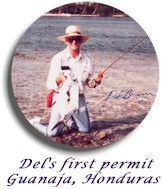

Del credits me with getting him started in big game fly-rodding which ultimately lead him to giant jungle tarpon, billfish in Costa Rica and Panama, bonefish in Belize, permit in Honduras and finally to the Florida Keys where he has taken all of the premiere flats species: tarpon, bonefish, mutton snapper, snook and his beloved permit. How so? Well, I took him tarpon fishing with me to Costa Rica in 1974, his first adventure of this sort. From that trip forth, there has been no stopping this 78 year old saltwater veteran. He is now, without question, the consummate traveling angler, spending an average of 100 days a year fishing the flats of the Florida Keys; and that doesn’t include time spent elsewhere on this planet’s watercourses, seas and oceans.

Del credits me with getting him started in big game fly-rodding which ultimately lead him to giant jungle tarpon, billfish in Costa Rica and Panama, bonefish in Belize, permit in Honduras and finally to the Florida Keys where he has taken all of the premiere flats species: tarpon, bonefish, mutton snapper, snook and his beloved permit. How so? Well, I took him tarpon fishing with me to Costa Rica in 1974, his first adventure of this sort. From that trip forth, there has been no stopping this 78 year old saltwater veteran. He is now, without question, the consummate traveling angler, spending an average of 100 days a year fishing the flats of the Florida Keys; and that doesn’t include time spent elsewhere on this planet’s watercourses, seas and oceans.

While I have only taken one permit on a fly I have chucked a bug or two at them during the course of the last decade. In fact, the first time a permit rattled my knees and shattered my nerves I was sharing the boat with Del Brown. The fish I cast to was a monster and the best I could do was get it to tail on the Puff I threw at it. I thought my heart was going to stop and it was a grand high despite the fact the critter wouldn’t eat.

While I have only taken one permit on a fly I have chucked a bug or two at them during the course of the last decade. In fact, the first time a permit rattled my knees and shattered my nerves I was sharing the boat with Del Brown. The fish I cast to was a monster and the best I could do was get it to tail on the Puff I threw at it. I thought my heart was going to stop and it was a grand high despite the fact the critter wouldn’t eat.

Since that time I’ve spent a great deal of time talking with Del Brown about what it takes to take flats permit on a fly with a better than good degree of consistency. The following is what I’ve learned from the vast experience of the permit man. And believe me; I grilled Del like a homicide investigator trying to extract a confession!

Sixty of the 100 days a year Del spends plying the flats of the Florida Keys are in pursuit of permit. The rest are for stalking tarpon, reds, snook or bonefish. He has to his credit many large bonefish including one pulling the scale to 13-3/4 pounds. Big poons are no strangers either, with a 127-pound world record on 8-pound tippet, heading his list of flats tarpon credentials. Of those 60 permit days, only about 20 produce ideal conditions. Just what are those conditions?

Sixty of the 100 days a year Del spends plying the flats of the Florida Keys are in pursuit of permit. The rest are for stalking tarpon, reds, snook or bonefish. He has to his credit many large bonefish including one pulling the scale to 13-3/4 pounds. Big poons are no strangers either, with a 127-pound world record on 8-pound tippet, heading his list of flats tarpon credentials. Of those 60 permit days, only about 20 produce ideal conditions. Just what are those conditions?

Here’s what Del had to offer.

First and foremost is water temperature. The H2o covering the flats needs to be 70 degrees or higher for optimum numbers of permit to be there, despite the fact that they are more temperature tolerant than the other flats quarry. A fast moving cold front rapidly forcing the temperature downward can devastate angling opportunities even if the temperature remains well within the optimum window. For example, if the temps were in the 80’s and quickly dropped ten degrees to the 70’s, the resulting shock would chase most sickle-tails off the flat. With permit you need all the shots you can get. Opportunity is everything…

First and foremost is water temperature. The H2o covering the flats needs to be 70 degrees or higher for optimum numbers of permit to be there, despite the fact that they are more temperature tolerant than the other flats quarry. A fast moving cold front rapidly forcing the temperature downward can devastate angling opportunities even if the temperature remains well within the optimum window. For example, if the temps were in the 80’s and quickly dropped ten degrees to the 70’s, the resulting shock would chase most sickle-tails off the flat. With permit you need all the shots you can get. Opportunity is everything…

Cold fronts are not all bad, though, if they don’t cause radical water temperature drops. Usually high, bright skies ride the tails of a front providing the fly fisher with optimum visibility, the next single most important condition those in pursuit of flats permit must have. If you can’t see ’em, you can’t cast to ’em. I know of no one that can boast of taking a permit on a fly by blind casting to one. So, ideally, you need a bright cloud-free sky as one of the optimum conditions. Although this is not to say you can’t catch permit when skies are pocked with the billowy stuff. You’ll have to look for other signs then.

Next in the order of importance is wind – yes, wind. Can you imagine a saltwater fly fisher hoping for wind… Well, when it comes to ideal permit conditions incessant breezes ranging from 10 to 15 mph is considered perfect. Actually Del ranks 10 mph as best for him, but I know others that would opt for 12 to 15.

The wind is what provides permit a sense of security when they venture onto a shallow flat to feed. Let’s face it – these critters can be big – garbage can lids with fins. They have to feel a little conspicuous when they range onto a shallow flat perhaps less than two feet in depth. Mild blusters also stir up the bottom a little, kicking out goodies like shrimp, crabs and myriad other critters that permit call food.

Next to wind, tides are an extremely important factor. Del Likes “Spring” tides best, which result in big pushes of water. Permit will move on to a flat, working the down current side of a bank as the tide floods. Often they’ll range up onto a flat that normally wouldn’t hold them during a “Neap” tide. The availability of enough water, including deep water, such as a nearby channel is often crucial.

With the mention of food one might assume the next most important requirement would be the fly that represents permit fodder. Not according to Del. Next on the list is a good guide. I would have to agree with Del that once provided the optimum environmental conditions the next most important need is a top-notch guide who knows where to find this black-finned phantom of the flats. A good guide is worth every dime he or she earns. Skill and experience is everything: knowledge of productive flats, optimum tidal phases, where they will be on a tidal stage, which way they’ll be coming, what to look for – the list goes on. You can’t skimp on a good guide. Get the best one you can, one with a good reputation.

With the mention of food one might assume the next most important requirement would be the fly that represents permit fodder. Not according to Del. Next on the list is a good guide. I would have to agree with Del that once provided the optimum environmental conditions the next most important need is a top-notch guide who knows where to find this black-finned phantom of the flats. A good guide is worth every dime he or she earns. Skill and experience is everything: knowledge of productive flats, optimum tidal phases, where they will be on a tidal stage, which way they’ll be coming, what to look for – the list goes on. You can’t skimp on a good guide. Get the best one you can, one with a good reputation.

He goes on to say, “Most flats guides, whether or not they specialize in fly-rodding, include permit fishing in their flats repertoire. They may pursue them with live crabs instead of Merkins, but they know where the critters forage and can put you on a spot where opportunity will come a knocking.”

Okay, you’ve got great conditions and a highly ranked guide. What comes next? You – and your abilities, my prospective flats permit angler, are what comes next!

Okay, you’ve got great conditions and a highly ranked guide. What comes next? You – and your abilities, my prospective flats permit angler, are what comes next!

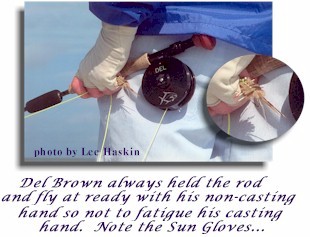

Many, out of jealousy, envy or whatever, come off with something like, “If I spent that much time fishing for permit, I’d rack up a hefty score, too.” Well, in my mindset, these bozos are off the wall. Indeed, opportunity is tantamount to success, but if you can’t capitalize when it presents itself you might as well be in the parking lot. In this vein, your casting ability is the number one consideration. You must be able to cast with accuracy to targets anywhere on the clock regardless of wind direction or velocity. “Seeing” is important, too, although your guide can help you out. “Never say you can see the fish if you can’t”, says Del. “Point your rod out over the water and the guide will direct you to point left or right, up or down until you are sighted-in with the rod’s tip”. “Never cast if you can’t see the fish unless the guide tells you to; and when he says “drop it!”, don’t make another false cast – drop it – like NOW!

One of Del’s tricks out of a bag of many, is to “water haul”, laying the line on the water on the fore-cast several times before the permit closes to a point where he must make the presentation toss. “Water hauling”, he explains, “allows me to judge the effects of the wind, letting me line up my cast.” “Of course, you don’t want to do this if the fish is within spooking range; and you absolutely can’t “rip” the line off the water.” “You can’t wuss it either, though.”

One of the biggest casting mistakes anyone makes when fly fishing the flats, particularly when the wind in up, is to be tentative with a cast. Like Del says, “Don’t wuss it!” You have got to move the rod tip with authority, punch the line into the wind or across it (whatever) on your backcast, coming forward with the same assertiveness. Trying to finesse your cast like on a trout stream will only result in disaster. Believe me, this goes for any flats fishing!

One of the biggest casting mistakes anyone makes when fly fishing the flats, particularly when the wind in up, is to be tentative with a cast. Like Del says, “Don’t wuss it!” You have got to move the rod tip with authority, punch the line into the wind or across it (whatever) on your backcast, coming forward with the same assertiveness. Trying to finesse your cast like on a trout stream will only result in disaster. Believe me, this goes for any flats fishing!

Now comes the fly.

Alright! You’ve got all the casting skills nailed plus everything else, except knowing which fly is best. There are two things that have really turned around flats permit fly-rodding from chancy at best, to predictably good. The first of those two are improved fly patterns. Flies that act like the food permit love to eat best – a small, juicy blue crab. Note: I said “ACT” like – not necessarily “look exactly” like a crab.

There are some flies that look as though they could crawl across the bottom on their own power, catch their own food and dig burrows. Problem is, however, they don’t drop right. That’s it! When crabs are swimming along and all of a sudden come face-to-face with a critter with jaws agape, intending it eat it, they don’t try to out swim the predator, they instead drop instantly to the bottom, claws up in a defensive posture, and remain almost motionless. Other crustaceans scatter like shrapnel from an exploding grenade, but crabs drop to the bottom to hide in sand, marl or grass.

Sure, looks help but it’s the slanting crash dive that makes the fly work. Del Brown’s Merkin does this better than any other permit fly being used today – and, it is really fairly easy to tie. There are other good bugs being used, flies created by some of the best. They don’t hold up against the Merkin, Though. Like I said, the numbers say it all…

Sure, looks help but it’s the slanting crash dive that makes the fly work. Del Brown’s Merkin does this better than any other permit fly being used today – and, it is really fairly easy to tie. There are other good bugs being used, flies created by some of the best. They don’t hold up against the Merkin, Though. Like I said, the numbers say it all…

Next is presentation. There are several different shots that you may have at permit: There’s the head-on target, the toss to broadside cruisers, the favorite, a cast to a tailing fish, and the desperation reach to going-away fish.

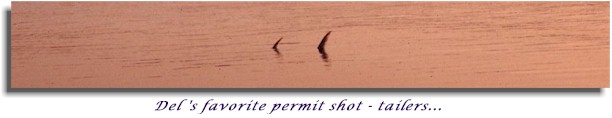

Del likes tailers best, although he’s taken fish from every situation. He also likes casting to just a few fish (a pod), or singles best. “When casting to a school of permit”, he says, “your chances of spooking an unseen fish are far greater than when casting to a small pod, or singles.”

With head-on permit Del likes to try to “bean” them, as it’s said. Put it right in line a foot or two from their nose. And, here comes the second most important thing besides the fly – the retrieve. Strip the fly until the fish sees it and then drop it straight to the bottom and don’t move it unless the fish starts to turn away. It is the “NO” retrieve that works the best, making the fly act just like the real thing. I can’t over emphasize this. Imperiled crabs don’t try to out swim permit!

If the permit rushes over and tails on the fly, wait a second (I know it’s hard) and then make a slow steady pull with your stripping hand. If you feel any weight or resistance, set the hook with a stiff pull of the line hand along with a hard, low, side sweep of the rod.

When Del took his 41-pounder, he dropped his Merkin so close (he almost did bean it) that he was afraid to move the fly. The fish was tailed-up and Del knew he had to do something. He made the slow strip, felt weight, set the hook and both he and Steve Huff knew they had the right fish on… About an hour later Del had the new world record on 8-pound.

When Del took his 41-pounder, he dropped his Merkin so close (he almost did bean it) that he was afraid to move the fly. The fish was tailed-up and Del knew he had to do something. He made the slow strip, felt weight, set the hook and both he and Steve Huff knew they had the right fish on… About an hour later Del had the new world record on 8-pound.

For broadside cruisers, singles, pods or a school, drop the fly just beyond and about five or six feet in front. Strip once or until you get a fish’s attention and then drop the fly. The rest you know.

Tailing fish: drop the fly as close as you can without actually hitting it. Why try to bean it then? Well most casters can’t hit it on purpose but will come close, which is what you want. You get the picture.

Permit, singles, pods, or schools that have gotten by you requiring a cast to their tails are obviously not the optimum opportunity. None-the-less, Del still has taken many permit by casting to their flanks, even if they are heading the wrong way. Permit have enormous eyes for their size for a good reason. It’s to see things with greater efficiency, critters that may be trying to escape to the rear. Drop the fly a couple of feet to the side of the fish, pull the bug until you draw a fish toward it and then drop it.

Of course knowing how to “read” a permit always helps when determining when to drop the fly or set the hook. This takes experience; but then that’s why you have a good guide.

NEVER take your eyes off the fish but ALWAYS keep an ear toward your guide! Do what your captain says without hesitation!

What do you do once the critter inhales your fly and you’ve stuck him? Forget about the fish! Clear line – get it on the reel fast without tangles and snarls. Once you are fighting the fish off the reel most of the worries are over. Permit have a soft but tough mouth, meaning the hook penetrates easily but unlike with tarpon, the fly rarely pulls out. They’ll make a blistering run, usually for deep water, that channel or cut they originally ventured onto the flat from. Once in deep water they’re fighting tact is similar to any large jack – broadside against the strain of the pull. Keep playing the angles whenever you can.

What about seeing permit? If you can’t see them then correct presentation becomes a moot issue. The highly conditioned eyes of your guide will be the primary spotter until you get some experience at what to look for. This should help though: The angler should not try to look too far ahead. Scan closer, say out to a couple of hundred feet or less. Keep your eyes scanning both the surface and the bottom – the surface at a distance, the bottom in close.

What about seeing permit? If you can’t see them then correct presentation becomes a moot issue. The highly conditioned eyes of your guide will be the primary spotter until you get some experience at what to look for. This should help though: The angler should not try to look too far ahead. Scan closer, say out to a couple of hundred feet or less. Keep your eyes scanning both the surface and the bottom – the surface at a distance, the bottom in close.

Don’t fix your eyes in one spot unless you think you’ve spotted something and then alert your guide. He may be looking in another direction. Look for black, sickle-like tails and fins piercing the surface, flagging in the wind; look for black fins and tails and a big eye without a body, a ghostly image, caused by silver sides reflecting the environment around it. Nervous, shimmering or waking water tells a story, too. Once you learn to recognize a permit wake, you’ll never mistake it for one made by another critter.

As it is with most marine fly-fishing, timing IS EVERYTHING (luck counts heavily, too)! The best months for permit fishing on the flats range from late February until the end of April, with March probably being the peak.

Another reason I haven’t chased permit: May and June are tarpon months, and while a few permit are around, most are offshore spawning then. So, plan your trip accordingly.

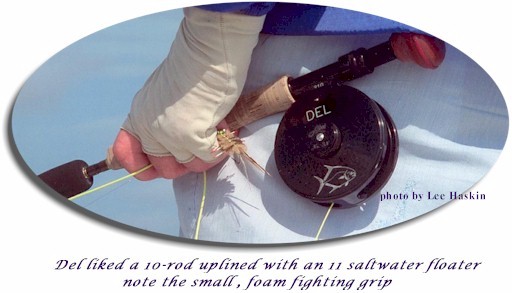

When it comes to tackle, Del prefers a nine-foot, ten-weight graphite rod, up-lined with an eleven, weight-forward, floating line. He likes a standard WF over a Saltwater Taper or a Tarpon Taper. The reason for the 11-weight line instead of a ten, is to load the rod properly for average casts of 65 feet or less, and to handle the lead-eyed Merkin.

Favorite reels include the Abel 3N when using tippets testing less than 12 pounds. Anti-reverse jobs like a Billy Pate with a palming rim are touted, too, as well as the enduring Sea Master of which he has several.

Favorite reels include the Abel 3N when using tippets testing less than 12 pounds. Anti-reverse jobs like a Billy Pate with a palming rim are touted, too, as well as the enduring Sea Master of which he has several.

In addition to the fly line, Del likes to load his reel with (starting with the back of the fly line, working toward the arbor) 50 yards of 20-pound, hi-vis mono to reduce line drag (its slicker), and to provide some shock absorption when using light tippets. It is also less abrasive to the fingers when the fight draws close. Next, in 50 yard increments: white Micron, blue Gudebrod Dacron and finally white Micron again. He Joins these sections together with back-to-back Uni knots which must be paraffined to keep from burning the line when the knots are drawn tight. Why go through all this trouble? Del feels he is in better control throughout the battle by knowing just how much line and backing is out of the rod tip. He has never gotten into trouble using 20-pound backing on the flats, feeling you should be fighting the fish off the fly line, not the backing.

Leaders for Del are simple affairs. He likes them around ten feet in length: six feet of 50, two feet of 30, two feet of 20, and at least 24 inches of class tippet. He uses a Blood knot or a Surgeon’s knot to join the sections.

When using tippets of 8-pound or less he employs a Bimini leader system including an abrasion leader. Twelve and up, he omits the bite. With bite leaders he’ll use a Homer Rhodes loop knot to attach the fly [note: I’m sure today, if Del were alive, he would be using a Kreh Non-slip Mono Loop]; without, a Uni loop knot. “Do not use a clinching knot”, he says. “It will inhibit the proper dropping of the fly.”

Excuse me folks the phone is ringing…

“Hi, Del! What’s up?”

I’m back. I just got off the phone with Del Brown – speaking of the Devil. It’s March 6th and he is in Marathon. Yeah, he’s been fly-fishing for permit again. He just checked in to give me a report. He does that a lot. He says he’s added a few more fly rod permit to his total – all of which were taken on the flats. You see, Del doesn’t fish for deep-water permit – ever!

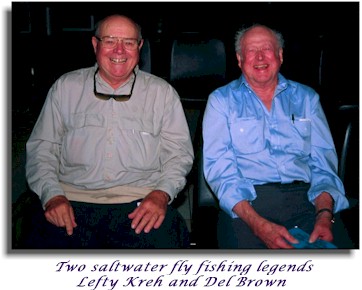

What more can I say except that Del Brown is among the world’s most respected fly fishing legends and his contribution to fly fishing for the coveted permit will probably never be equaled.