It was a couple of hours past sunrise on a mid-October morning, the day of the new moon, when guide Brian Esposito poled me and my wife, Sue, into a shallow bay lined with roso-cane. We were in the Louisianamarsh near Venice, where the main stem of the Mississippiflows into the Gulf of Mexico. We had already seen a few of the giant redfish we traveled to Louisianato hunt. I’d taken a couple of shots but got no bites.

Part of the problem was inaccurate casting on my part, but another reason for the lack of hook-ups was the way the fish were behaving. Instead of floating on the surface or cruising high in the water column like they normally do during the fall, the reds seemed to be swimming low in the discolored water, surfacing occasionally for just a few seconds, and then dropping out of sight again. Brian blamed this behavior on unseasonably warm water temps. It wasn’t cold enough for the fish to want to warm themselves on the surface.

Suddenly, just off a small point about 40 feet to the left of the boat, a large fish popped to the surface, swirled and swam directly toward us. I cast, and then watched in admiration as a mammoth wake transformed into a gaping mouth that inhaled Brian’s chartreuse and white “big-fish” fly.

I set the hook with a strip-strike, and then pounded the fish again by sweeping the rod tip low to the side several times.

For the next few minutes, I had the pleasure of tangling with a large and extremely pissed-off beast. The fish put itself on the reel on the first run, and then dashed from side to side, shaking its head and thrashing around. I worked it close to the boat several times by pumping the rod and reeling in line, but each time I got it close, the fish would surge away with renewed strength, testing the 20-pound tippet by pulling out more line and making my Tibor Everglades sing. The fish never got into the backing, but it did take most of the fly line on several runs.

On his first pass near the boat, I could easily tell it was the largest redfish I’d ever seen, much less had on the end of the line.

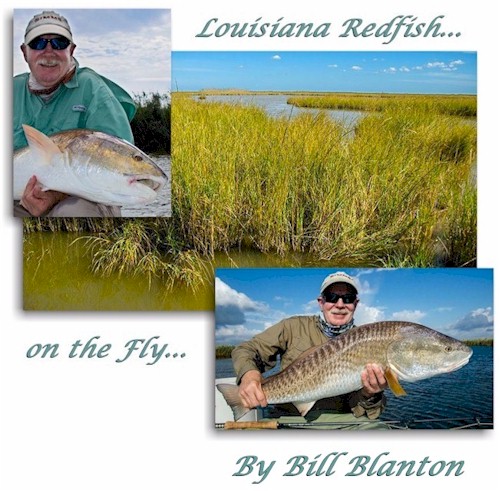

After about 10 minutes of give and take, the fish finally rolled on its side. I pulled it closer to the boat. Brian captured it with a Boga Grip and quickly weighed it. At 30 pounds, it was three times heavier than my previous best, a 10-pounder taken in the Everglades more than a decade ago.

In my arms, waiting to have its picture taken, the red was so round and thick, I had trouble holding it. A 30-pound redfish is longer than a 10-pounder, but it’s also disproportionately bigger in girth. I could grasp the narrow part of its body just before the tail with my right hand, but there was no way I could hold the head of the fish with my left hand. I ended up sitting on the forward casting platform, resting the fish on my knees and trying, not too successfully, to pose its head with my left hand while it slid around in my lap. It was sort of like wrestling a very large, very slippery, very active bag of flour.

In my arms, waiting to have its picture taken, the red was so round and thick, I had trouble holding it. A 30-pound redfish is longer than a 10-pounder, but it’s also disproportionately bigger in girth. I could grasp the narrow part of its body just before the tail with my right hand, but there was no way I could hold the head of the fish with my left hand. I ended up sitting on the forward casting platform, resting the fish on my knees and trying, not too successfully, to pose its head with my left hand while it slid around in my lap. It was sort of like wrestling a very large, very slippery, very active bag of flour.

With my personal-best redfish caught, photographed and released we set off to wrangle up more giants. For the rest of the fishing day, however, we only saw a few fish and none in a really good position for a cast.

Speaking of casting, after 18 years of working tangled mangrove shorelines in the Everglades and presenting flies to spooky fish on inshore flats, I consider myself a pretty accurate caster. I don’t have any trouble threading a cast through mangrove branches or laying a fly gently in front of a tailing red on a skinny-water flat; however, the marsh redfish in Louisiana present a different challenge. They are intently focused on the area right in front of their face and oblivious to pretty much everything else. Though they’re extremely eager eaters, generally speaking, they won’t swerve to left or right to pursue a fly. If a cast is too short, even by inches, they won’t look at it. Same for a cast that leads a traveling red too far. The sweet spot is an area a few inches directly in front of the fish’s face. The ideal cast is one that presents the fly just beyond a swimming fish and a retrieve that pulls the fly toward the fish and directly in front of its mouth.

That cast would spook a Florida redfish right out of its spots, but the ultra-close presentation is the only thing that will consistently get a marsh red’s attention.

On the second day of our four-day trip, we decided to leave the big fish alone and try for more hook-ups with smaller fish. The terms “large” and “small” have unique meanings in the Louisiana marsh. A “large” fish is anything over 10 pounds and up to 40 pounds or more. A “small” fish is anything under 10 pounds, but many of those smaller fish are seven- and eight-pounders that would be considered trophies for inshore fly fishermen in other locales.

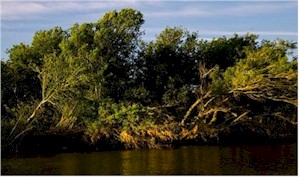

We headed deeper into the marsh, away from the roso-cane bays near the Gulf and into narrow creeks lined with Spartina grass. The tide was low in the morning, coming in all day. We followed it into the creeks, with Brian poling in water that was only inches deep. At times, he’d pole until the boat mired on the bottom, then wait for a little more tidal flow to float us off.

Everywhere we went reds were dining on shrimp skittering across the surface. Quick, accurate casts were essential, but the fish were ravenous. On one occasion a fish gobbled one of Brian’s shrimp imitations as soon as it touched the water, like a freshwater trout taking a dry fly off the surface. In a couple of instances, fish actually surged – almost jumped – out of the water chasing a fly that had been retrieved too fast.

We caught a ton of redfish, mostly in the seven- to eight-pound range. Sue captured her largest-ever fly-caught red, a beauty with multiple spots.

We caught a ton of redfish, mostly in the seven- to eight-pound range. Sue captured her largest-ever fly-caught red, a beauty with multiple spots.

Later that day, out closer to the Gulf, we saw some larger fish but didn’t have good shots at them.

On days three and four, we headed back to big-fish country, looking for giants, but conditions weren’t kind. The wind picked up and skies turned overcast, yet the water stayed too warm to lure many fish into the marsh. We covered miles of water as Brian used his trolling motor to scour big-fish bays near the Gulf. On the morning of day three, I caught a fish that was right at the tipping point between small and large, a 10-pounder that put a good bend in my nine-weight and showed me what the back end of my fly line looked like.

for giants, but conditions weren’t kind. The wind picked up and skies turned overcast, yet the water stayed too warm to lure many fish into the marsh. We covered miles of water as Brian used his trolling motor to scour big-fish bays near the Gulf. On the morning of day three, I caught a fish that was right at the tipping point between small and large, a 10-pounder that put a good bend in my nine-weight and showed me what the back end of my fly line looked like.

We caught some small fish during the day, then, later that afternoon I had one of those opportunities that linger in your dreams long after the trip is over. Just as we entered a bay, we saw a large fish swimming toward us, right on the surface. It was about 120 feet away when we first spotted it, giving Brian plenty of time to position the boat and me plenty of time to get ready. When it was about 60 feet away, I cast and watched the line unroll on target. The fly landed right in front of the fish. It charged … then spooked.

We caught some small fish during the day, then, later that afternoon I had one of those opportunities that linger in your dreams long after the trip is over. Just as we entered a bay, we saw a large fish swimming toward us, right on the surface. It was about 120 feet away when we first spotted it, giving Brian plenty of time to position the boat and me plenty of time to get ready. When it was about 60 feet away, I cast and watched the line unroll on target. The fly landed right in front of the fish. It charged … then spooked.

Either the cast was too close or the initial strip too aggressive — one way or the other, the fish was gone.

Day four was windy and overcast with rain storms threatening. Once again, we scoured the bays, seeing no fish at first. Then, all of a sudden, two fish surfaced about 100 feet from the boat. Brian closed the gap with the trolling motor, and I shot off a cast that landed just right, with the fly about three feet on the far side of the fish. I retrieved the fly past the lead fish’s nose. It followed and ate.

On the initial run, the fish acted more like a snook than a red, dashing rapidly toward the cane. I guided it away from the roots and led it out into the open water while Brian backed the boat up a bit. A few powerful runs later, we had it at boat side, where it tipped the Boga at 18 pounds.

On the initial run, the fish acted more like a snook than a red, dashing rapidly toward the cane. I guided it away from the roots and led it out into the open water while Brian backed the boat up a bit. A few powerful runs later, we had it at boat side, where it tipped the Boga at 18 pounds.

The rest of the day was frustrating. We journeyed from bay to bay, searching for fish, seeing nothing. Around mid-day, the rain hit. We scrambled into rain gear while Brian pulled the boat up against a cane bank to wait out the storm. After an hour or so, we were on our way again, but fish were still scarce.

Late in the afternoon, Brian poled out onto a shallow bar in the main stem of the Mississippi. The light sandy bottom was like a bonefish flat, but the wind whipping across it churned up a chop that made fish-spotting extremely difficult. Finally, Brian glimpsed a fish at two o’clock about 40 feet away. I fired off a cast — too short — then another that was on the money, and we were hooked up again.

With the morning’s 18-pounder still fresh in my mind, I thought this fish was on the small side, so I tried to horse it in. That didn’t work — it wouldn’t horse. Instead, it made strong runs, then dove under the boat, then tried to wrap the leader around Brian’s push pole. When we finally got it to the boat It was another 10-pound fish, and a great way to end the trip.

This was Sue’s and my first trip to the Louisiana marsh, so we really didn’t know what to expect. We brought an arsenal of rods from TFO, Hardy and G-Loomis — four nine-weights and two 10-weights — along with a huge assortment of flies of every description — Deceivers, Clousers, crab patterns, spoon flies, sliders, divers, poppers, etc.

With all that gear at hand, I used a single rod, my one-piece Hardy Proaxis nine-weight, loaded with a Rio Tropical Outbound Short floating line. I was able to transport the one-piece rod since we made the 1,800-mile round trip from our home in South Florida by car rather than air. We used only four flies, all Brian’s and all variations on a very simple pattern. The tail was a craft fur strip with the backing attached, sort of like a synthetic Zonker strip. The body was Enrico Puglisi’s Tarantula Hairy Legs brush-palmered around the hook like a dry-fly hackle.

The big-fish fly was chartreuse and white on a 2/0 hook. The small-fish fly was all brown on a size one hook. A shrimp variation of the small-fish fly added plastic eyes and was tied in shrimpy-looking colors. The most effective for us was all white. All flies were tied un-weighted. If weight was needed, Brian would wrap a little lead wire around the hook just behind the eye.

That’s about as simple as you can get, but still very effective in the Louisiana marsh.

Like many of the other fly guides working out of the Venice area, Brian is based in Florida. He guides the marsh during October and November, and then guides Biscayne Bay, the Keys and the Everglades the rest of the year.

We were in Louisiana only six weeks after Hurricane Isaac pounded the area. Driving the 80 miles from New Orleans to Venice on a highway that traverses a narrow strip of land between the levees, we saw remnants of Isaac’s wrath — muddy areas that had been covered with flood waters, damaged or destroyed houses and trailers, boats stranded on highway medians. Venice itself appeared to have experienced only minimal damage.

We were in Louisiana only six weeks after Hurricane Isaac pounded the area. Driving the 80 miles from New Orleans to Venice on a highway that traverses a narrow strip of land between the levees, we saw remnants of Isaac’s wrath — muddy areas that had been covered with flood waters, damaged or destroyed houses and trailers, boats stranded on highway medians. Venice itself appeared to have experienced only minimal damage.

The marsh itself seemed healthy, just waiting for cooler water to lure the giant redfish inshore from the Gulf. The only real signs of disaster were man-made, the incredible amount of debris and abandoned works left by the oil industry — capped off wells, rusting barges, rotting docks and pilings. Some of the abandoned works were constructed on dry land, but, asLouisiana’s coastline has receded, they’ve been covered by water. Now they are navigational hazards as well as potential environmental concerns.

It was a wonderful trip and experience on all counts and I’ looking forward for a return trip to the wonderful Louisiana Marsh for more redfish wrangling with a fly rod.

It was a wonderful trip and experience on all counts and I’ looking forward for a return trip to the wonderful Louisiana Marsh for more redfish wrangling with a fly rod.

Guide/booking information: